What to do with stormwater in your landscape and the greater landscape

So I have an infomercial question for you today.

Do you want to cut your water bill and usage by 50%? Stick around and I’ll show you the no-brainer solution! But wait, there’s more! You’ll get several other bonus tips at no additional fee!

Just ten easy payments….

I’ll stick to blogging.

With all this talk on stormwater, I have broken stormwater management into segments based on geographical categorization. We already talked about stormwater in the urban center and several strategies related to urban areas.

So why the breakout? Is there really a difference in management strategy between urban, rural, and suburban? Aren’t I really just talking about keeping water on the land to percolate more slowly?

In short, yes and no. I know that helps explain nothing.

There is significant overlap in strategy between geographical areas, especially between urban and suburban areas. However, each of these areas are different enough in how they were designed, planned, populated, and used that they warrant a specific set of strategies tailored to their geography and planning.

Similarly, proper management of water is something so crucial in sustainable landscape design, yet so tragically misunderstood and ignored in conventional design. This is why it is so important to understand the unique qualities to each of these areas as specifically as possible without writing a full book.

About the ‘Burbs

I grew up in an early, aging suburb of southwestern Ohio, and I now live in a younger suburb that has engulfed a smaller town outside the city. We moved into a house built in the mid-1970s that backs up to an 83 acre farm. One of the last remaining farms in the area, it is currently being developed with expensive homes by a large developer. The development has eight home layouts from which to choose.

Such development and planning is typical of the suburbs. For better or for worse, suburban areas are developed piecemeal as populations grow and trends rise and fall in various extra-urban areas. The end result is an amorphous growth of residential, commercial, and industrial pockets outside the city center in ever growing concentric areas.

So with that said, let’s look into what characterizes a suburban area. For this, I’ve consulted the semi-omniscient Wikipedia.

Here are some characteristic elements of typical suburbia:

- Subdivisions

- Shopping malls

- Strip malls

- Property zoning

- High percentage of single-family units

- Higher population density than rural areas, lower than urban areas

What we get with suburbs is a patchwork expanse of residential, commercial, and industrial areas developed upon former farmland, swampland, forest, and grassland as the population centers expanded.

I offer no critique here but rather want to paint a picture of our suburbs for better understanding of infrastructure and continuity throughout. This will provide the basis for measures that can be taken given the existing development. This discussion would be entirely different if we were talking about new urban planning or community design, but instead here we are focusing on what to do with our suburbs as already established.

Here are some resulting characteristics of stormwater management in the suburbs:

- Culverts

- Tributary creeks with eroding banks

- High percentage runoff from roofs, lawns, and pavement

- Need for irrigation

- Sewer overflows

- Flash flooding

- Drought conditions

What we can do

As is the case in nearly all human developments, stormwater in the suburbs is designed to leave the developed area as quickly as possible. Clean water use within buildings is designed as single use.

The following strategies are designed for the opposite effect: to hold and absorb as much water into the landscape and to layer as many uses as possible within buildings.

With the implementation of these strategies in a way that incorporates a holistic design process, the result is a designed suburban landscape that is capable of supporting environmental health through reduced erosion, increased water absorption, and increased buffering capacity of temperature and moisture.

How we do it

As the management strategies differ with each land use type, I’ll discuss each separately. That is, what we do in a residential area differs from a commercial area, from industrial and public areas. Each space has unique characteristics.

Stormwater Management for All Land Uses

Lose the Lawn

If it hasn’t been apparent in some other articles, I’m not the biggest fan of the conventionally perceived lawn. What is the ‘conventionally perceived’ lawn? I’m talking the one that most people have – a lawn with a dominance of one or a few varieties of grasses, where any broad-leafed plant is the archenemy of the suburban homeowner.

We have this perception that a lawn has to only be grass, nothing else. Heaven forbid a stray clover seed waltz into the soil on our property and decide to germinate and tempt us with those little white flowers!

This wasn’t always the case. In fact, up through and shortly after World War II, the quality of a seed mix was once judged by how high a percentage of clover it contained – as admitted by the main proponent of the first broadleaf herbicide (2,4-D):

“I can remember the day when lawn mixtures were judged for quality by the percentage of clover seed they contained. The higher this figure, the better the mixture. . . I can remember the loving care which old-time gardeners gave their clover lawns.”

Reginald Milton Carleton, A New Way to Kill Weeds, 1957

It was through the marketing of this very herbicide that we have come to perceive the idea that lawns must be free of all things except grass.

But this is a problem. Too much of any one thing is a system weakness. It opens the way for disease, overuse of resources, and various other problems. These attributes apply to the modern lawn.

Think about it. We cultivate a plant descended from ancestors that grew in a diverse array of mixed species, where it grew several inches or feet tall. Now we propagate it and plant it in an expansive carpet, trim it regularly at a few inches high, and expect it to be healthy. But it isn’t. Enter the herbicide and fertilizer industries with gleaming eyes and product in outstretched arms.

I probably have some of you nodding in agreement, and some of you steaming with frustration.

I’m just pointing out here that we’ve been patterned since birth to expect this part of a landscape. At the same time, we’ve been sold on very effective marketing that this is the way it is, your lawn has to be like this in order to be a self-respecting member of society, so buy our fertilizer, seed, trimmer, mower, herbicide, service, etc.

So let’s take a deep, slow breath and think logically. Is having a lawn really necessary? Most would say no. But most would also say at least one of the following:

- It’s attractive

- Easy to maintain

- Need somewhere to relax/play

- Best option as an attractive ground cover

- Required to have a weed-free lawn by my HOA

Well, I think we can provide logical and time-saving alternatives to the first three. For the last one, sorry. That’s something you need to work out on your own turf.

This isn’t a lawn article. But you can be sure I will be writing on this further in the future with some tangible solutions, alternatives, and good solid examples.

For now, you can choose to agree, disagree, or remain indifferent. So I’ll end with a few lawn factoids:

There are many flowers and low growing plants that provide a beautiful alternative to the conventional lawn

- Lawns cover an estimated 40 million acres of the United States.1 Wheat covers 45 million acres. Corn 84 million. 2

- Lawns by their nature sequester carbon. This is offset by mowing, irrigation, nitrogen, and herbicide inputs.

- Trees, shrubs and other groundcovers sequester more carbon

- Outdoor watering accounts for 50-75% of total household use in many areas.1

- Compared to unplanted surfaces, lawns reduce surface runoff and erosion

- Compared to other planted surfaces, lawns show greater runoff and erosion

- In 2007 alone, approximately 16 million pounds of 2,4-D (broadleaf herbicide) and glyphosate (RoundUp) were used in residential applications3

- The average adult spends over 40 hours per year on lawn care4

We spend so much time, effort, and money trying to maintain a very un-natural system and keep the natural process at bay. Folks, nature is an unstoppable force. And it’s trying to tell us something. The big win is when we work with nature in a way that is aesthetically pleasing.

So ditch the lawn. Or as much as you can part with.

Proceed with Plantings

Mixed plantings are almost always better than a lawn and certainly better than a hard surface for catching, slowing, and absorbing runoff. When planned with conscious accounting for stormwater runoff, plantings can not only reduce storm surges and erosion, but can also enhance the aesthetic value of the site. That is the goal here anyway. Provide function and a pleasant experience.

So how do we plant to help reduce runoff and erosion? Here are a few ways.

- Grouped plantings mix multiple species, functions, and growth habits together to provide a diverse approach to dealing with water.

- Overstory plants protect the soil underneath from direct rain, reducing erosion from direct heavy rains.

- Herbaceous plants (plants without woody stems, which often die back each year) commonly have shallow but very dense root networks that bind the soil and hold it together. An additional benefit to herbaceous plants is the organic matter they add to the soil each year as they move through their yearly life cycle.

- Grouped plantings can be designed on contour or in depressions, where they prevent or slow water runoff as it leaves a landscape. This allows absorption into the planting area to benefit the plants by catching water and any organic runoff. It also benefits the overall landscape and waterways by decreasing storm surge erosion and water loss.

- Ground covers can be effectively used on slopes from slight to severe for reduction of erosion and water loss. As with grouped plantings, ground covers provide a dense root mass to anchor soils and continual addition of organic matter deposited in the soil. Lawns do fall in this category, but the conventional short-cropped lawn is much less effective than various low growing ground cover plants or even prairie-style plantings.

Strategize Slopes

We currently fail to manage slopes by deliberately creating it to direct water quickly and efficiently to retention ponds and storm runoff waterways.

While this has its perceived benefits as discussed in previous posts about stormwater, designed slopes have added to compound problems in the immediate landscape and in the greater environment as a whole. To highlight these problems again, they include drought conditions, flooding conditions, erosion, and need for continual maintenance.

Instead, we need to design slopes that continue to protect the built environment while also reducing stormwater runoff and erosion.

Earthworks are an important way we can adjust slopes to slow or halt runoff. I briefly described some of these tactics in the Urban Stormwater post, and will describe them in much more detail in the upcoming Rural Stormwater post. However, I’ll provide a brief discussion here as well:

- Swales are simply ditches built on contour to halt runoff and allow absorption of water into the soil. The soil that is removed to create the ditch is formed into a gentle berm on the downhill side of this ditch. This provides a planting surface for trees and shrubs, with a passive irrigation catchment system created by the ditch. Very effective and if done properly, attractive.

The idea is to catch and hold water within the landscape, or to at least slow its exit from the designed landscape. This is counter to conventional design but provides multiple benefits. Some are as follows:

- Reduced impact on stormwater systems during surge events

- Minimized soil erosion

- Retention of organic matter to increase soil health

- Replenishment of local groundwater systems

- Increased moisture retention in soil

- Decreased need for irrigation/watering

- Lower landscape maintenance due to these factors

Managing lawns, plantings, and slope are themes that can be used broadly across all types of land use. Now let’s look into more specific land use types and some various strategies to be applied in each space.

Stormwater Management for Residential Land Use

Rig up Rain Harvesting

Houses in the suburbs pose a perfect opportunity for the catching and storing of rainwater. Right now, most houses are simply rigged with downspouts that direct water quickly off of the roof and away from the foundation.

Rainwater runoff is a massively wasted resource.

To repeat a previous statistic: Outdoor watering accounts for 50-75% of total household use in many areas.1

Half of our water is used outdoors! Does it really need to be city water – processed, cleaned, and chlorinated?

So here’s how you can cut your water bill by 50%…. Rainwater harvesting!

Most of us have heard about local rain barrel workshops, where you go and learn how to set up a rain barrel system on one of your downspouts to catch and store some water. These are a great start to begin realizing the convenience of stored rainwater.

But there’s a slight problem if you want to get serious about rain water harvesting. The most common rain barrel size is somewhere around 55 gallons. Let’s see how much rain it takes to fill a 55 gallon rain barrel.

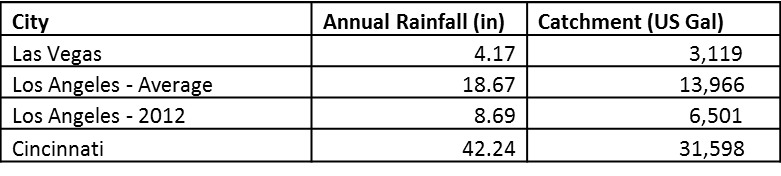

The average house in the US is 2,392 square feet. Accounting on the safe side and saying that most of those houses are two stories, let’s say that the average footprint and roof coverage of a house is 1,200 square feet.

So at 1,200sf here are the volumes of rain water that hit a roof during various rain events:

So even at a 0.1in rain event, we are overflowing our 55 gallon rain barrel. And what about that 1in rain event? That’s still a ton of lost water – actually almost 3 tons.

So the bigger the rain harvesting system, the more fully you will utilize your house to save on your water bill.

Just for a bit of understanding, here are the gallons of annual precipitation that hit a 1,200 sf roof in various parts of the US:

The amount of rain water captured in different American cities by a rain barrel for a 1200 sf roof over an annual period

So even in the recent drought conditions of southern California, or the normal conditions in Las Vegas, the average household can capture over 3,000 gallons of water given the right infrastructure.

But not many people want a few thousand gallon tank sitting around their property. So here’s my advice. Get the biggest rainwater tank system you’re comfortable with. And get one as aesthetically pleasing as you like.

What about all of that extra overflow water, then?

While rain harvesting gives us an accessible irrigation reservoir, the most effective way to capture and hold water is on and in the ground itself.

The earth structures I refer to are passive systems deliberately designed to capture and hold water. These systems, once installed, are incredibly resilient and require minimal maintenance if properly designed.

We already have touched upon this in the urban stormwater article as well as above in the ‘slope’ management section. So I’ll keep this one brief.

Suburban areas have the advantage of more space and less built infrastructure, allowing for more widespread implementation of effective small scale earthwork systems for capturing water in the landscape.

All in all, know that earth structures can be incredibly powerful in regenerating a landscape, reducing maintenance and increasing soil moisture and fertility.

Geek out with Greywater

Just as in urban areas, capturing greywater from household use before it goes down the sewer pipe – or into the septic system – can be incredibly useful. Again, this can significantly decrease the need to irrigate the landscape if implemented appropriately.

Simply put, a greywater system takes water used in bathing, laundry, or sink use and diverts it to the landscape instead of to the drain. This helps prevent strain on the sewer systems and also multiplies the functional use of household water.

Many greywater systems that divert to the landscape have a small retention area with plants that will clean the water before it flows further into the landscape. Bulrushes and cattails are two great examples of plants used for this purpose.

When greywater is diverted to a retention and filtration space that is above grade of intended irrigation areas, it can then passively filter into the landscape to slowly nourish and water the landscape.

Stormwater Management for Commercial and Industrial Land Use

Raise the Roof Catchment

In commercial areas, we can utilize the large footprint of buildings to capture water that would otherwise flow into runoff retention and into the conventional stormwater runoff system. Since most buildings in the suburbs are designed with more lateral emphasis rather than the vertical emphasis of urban centers, we can use this to our advantage.

Think of the residential calculations for rainwater catchment above. Now imagine how much water hits a commercial or industrial roof – often tens to hundreds and sometimes thousands times larger. That’s a lot of water.

So what’s the benefit for the company?

Well, a first tactic could be a planted roof. There has been significant research and design done with green roof systems to show that they provide cooling in warm months and insulation in cool months. 5 The end result is a significant reduction in heating and cooling costs – often the most expensive part of facility energy inputs.

For large buildings, rain catchment systems can be designed into the roof framework or on the sides of buildings to be integrated into the cooling systems. The same integration could be done in industrial facilities that require water for their cooling processes.

Finally, catchments or ground level retentions and diversions can be installed without a direct benefit to the building, but a long term benefit to the facility grounds. When designed properly, all of that runoff water can be designed into the landscape as a passive irrigation system for beautification of the grounds at low or no cost.

Pimp out the Parking Lots

Parking lots take up a large amount of space in the commercial and industrial suburbs. This is again an opportunity to catch and redirect a lot of water to absorb into and irrigate the landscape.

Islands within lots can be designed to catch and store water for an aesthetic effect. Drainage can be designed to flow into earthworks that again will allow infiltration for long term irrigation of the landscape.

Most lots are graded to direct water off of the property, or into a drain that sends water off the property. Instead, grade the lot toward the main landscape.

Empower Employer/ Employee Benefits

Employers are often looking for non-financial ways to enhance employee performance. One such way is through a pleasant work environment. Similarly, customers enjoy a pleasant environment when visiting a business. Landscape beautification is often an expensive investment to install and maintain for this pleasant experience.

With conscious design through appropriate stormwater management and plantings and by following the principles of aesthetic ecosystem design, a business can enjoy having such a pleasant landscape experience while greatly reducing maintenance costs.

The public sector likewise benefits from conscious design in commercial and industrial landscapes due to the reduced load on stormwater runoff systems.

These landscapes can be designed as an employee benefit as well. By providing a pleasant landscape for employees to take a relaxing break during work hours, employee performance and satisfaction increases.

Stormwater Management for Public Land Use

The public sector takes the largest burden for stormwater, as it contains the infrastructure for stormwater management. Thus, as public facilities are built and designed, stormwater impact should be very carefully considered.

Road Design – Conscious Contour

In the design of new roads, land contours should be considered in order to aid in stormwater management. When roads follow contour and ridgelines with right-sized catch basins, there are several benefits in relation to rain water management:

- Reduced erosion of roadside ditches

- Reduced need for road sewer drainage

- Increased use of median and roadside for rain catchment and plantings

- Decreased impact on sewer infrastructure

- Reduced maintenance of roadways due to water issues and erosion

There is a lot that goes into road design, and I am not a professional in this area, but I do know that we can take better consideration of how they are planned in order to reduce impact on our storm water systems. The runoff from roadways alone is a significant amount that can be directed away from sewer systems and drainage creeks.

Commence ‘Curb Cutting’

Another strategy that can be employed on existing roadways is the practice of curb cutting. Think of it this way. Right now, roads are graded to have a slight hump in the middle so water washes towards the curbs. There, it runs along the curbside until it hits a storm drain where it adds to the stormwater problem.

Instead of allowing water to reach the storm drains, we can strategically cut into curbsides and install catchment basins for retaining and absorbing stormwater into the landscape.

Designer Brad Lancaster has implemented this practice in Tucson, AZ for the establishment of self-watering food systems with great success. The practice is now quickly being adopted in other municipalities as well, especially in dry and drought-prone areas.

Brad points out in this video, “This costs the city nothing, but we’re dramatically reducing flooding downstream. And it costs us nothing to maintain all of this abundant vegetation because there’s no irrigation inputs.”

This simple technique, combined with appropriately-sized catchment basins, can have a major reductive impact on stormwater runoff when applied on a widespread scale.

These combined strategies are several practical, cost-efficient, and established methods for reducing the destructive effects of stormwater runoff while enhancing the landscape. I encourage you to take action and account for the benefits of good stormwater design in your landscape.

What will you do? Leave a comment below and let me know what measures you can take!

“We need to take care of our home, and our home is this planet. Our more immediate home is whatever ecosystem we find ourselves in. And the more we can live in balance with the natural system, the more it will do the work. The less work we have to do. And I think we need to strive to do things in such a way that the natural resource base is at worst maintained, and at best enhanced.”

– Brad Lancaster

Additional Resources:

- Rainwater Harvesting Basics: //www.harvestingrainwater.com/rainwater-harvesting-inforesources/

- EPA Green Roofs Compendium: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-05/documents/reducing_urban_heat_islands_ch_3.pdf

Sources:

- Milesi, C. et al. 2005. Mapping and Modeling the Biogeochemical Cycling of Turf Grasses in the United States. Environmental Management.3:426-438 //secure.ntsg.umt.edu/publications/2005/MREDTN05/MappingCristinaMIlesi.pdf

- //www.epa.gov/agriculture/ag101/cropmajor.html

- //www.epa.gov/opp00001/pestsales/07pestsales/usage2007_3.htm#3_7

- //www.bls.gov/news.release/atus.t08.htm

- 2012. Looking Up: How Green Roofs and Cool Roofs Can Reduce Energy Use, Address Climate Change, and Protect Water Resources in Southern California. https://assets.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/GreenRoofsReport.pdf?_ga=2.198800943.1611665758.1521122251-2099649968.1521122251

Photo Credits – in order of appearance: Ben Hale, Nelson Minar, Connie Ma, Brett Chisum, Englepip, Zanshin Art, McKay Savage, Agrilife Today, Agrilife Today, MaryEllen and Paul, Jeremy Levine, SusanA Secretariat, Jaysin Trevino, Thomas Le Ngo, NYS Stormwater, Tommy Clark, David Crummey, Aaron Volkening

Leave A Comment